How We Source Simple Goodness Syrups

September 21, 2021

By now, you probably know that we grow the majority of our syrup ingredients on our 10-acre family farm, in Buckley, WA - and whatever we can’t grow is sourced from other ethical growers. But what do we mean by ethical growers? Do we buy organic? Do we buy local? Do we buy direct from the farmers? The answers are sometimes, sometimes, and almost always.

Sourcing is our most challenging and rewarding aspect of our business, and it’s complex. Our passion for healthy food, communities, and a healthy American food system got us into making food our business in the first place. As a company it is our mission to contribute to these 3 pillars: healthy food, healthy communities, healthy farms— with every product we make.

Our sourcing ethos hasn’t necessarily evolved since we started making our syrups and growing or foraging every ingredient ourselves. As the company grows and we require larger inputs of pure, whole fruits, herbs and spices to produce our beloved multi-note syrup flavors, it would be very easy to choose convenience over our company values. Over time Venise and I have evolved our priorities when sourcing outside our own farm but have always stuck to our principles.

So what do we look for when we buy food?

It isn’t as easy as saying, “we will only source from organic farms,” or “we only source from Washington farms”. These labels, while convenient, tell only part of the story of how a product is grown, how the land it is grown on is stewarded, who grows the fruit, whether it is even possible to grow certain things in our region, and who benefits from the product’s sale. In order to get the true story, you have to get to know the farm, and the farmer.

For instance, many of the family farms in our area cannot afford the expensive certification process to label their foods as organic. Here at Simple Goodness Farm we farm using regenerative agriculture practices. Such practices like crop rotation, heavy duty weed fabric to reduce plant competition with weeds and prevent spraying chemical weed killers, and drip irrigation to reduce water use and prevent plant disease, are all "organic" practices. However, these practices alone do not qualify us to be officially labeled as an organic farm, which would require a significant monetary investment.

Many other farms prioritize the organic certification for only their primary money-making crop. An example of this is Sidhu Farms in Orting, WA, from whom we often buy our blueberries, raspberries, and strawberries. Sidhu Farms has only paid to certify their blueberries as organic, when in reality, the way in which they farm all their 12+ varieties of berries is virtually the same. The organic label is a helpful marketing tool for Sidhu farm’s blueberries, but not every crop’s yields and income justify the investment in the label certification.

In addition, these days the organic food industry is a billion dollar industry whose labeling simply does not say it all. Many organic megafarms are still factory farms who grow only one crop, do not focus on soil health or water conservancy, and use organic pesticides at large volumes (as is allowed by their certification.)

To dig a little deeper into the (hopefully well-nourished) dirt, below is a set of guidelines we’ve etched out for ourselves over the years, and consider for each sourcing decision:

- Healthy food: The harvest is as close to nature as possible, fresh, and free from toxic additives

- Healthy farms: Is the farm growing without the use of chemical pesticides? Are sustainable/regenerative agriculture practices used on the farm? Is it a family-owned farm? Is the farmer profiting the most off their crop, without losing the profits to middlemen in between us and them?

- Healthy communities: We believe that more, smaller farms growing many types of foods leads to a robust, privately owned, American grown, diversified food system. This gives our communities greater access to agriculture, both the products and the people, and educates our communities about where their food comes from. We want to invest in the rural communities where most food is grown. To support rural economies, we seek out family run farms, where we know that the money we spend goes to the farmers, who will then spend it on their family’s needs, and around their towns.

Despite challenges incurred by ever-changing harvests and supply, we will continue to source our syrup ingredients this way. As coach Jimmy Dugan said in A League of Their Own, “If it wasn’t hard, everyone would do it. It’s the hard that makes it great.”

Also in Blog

Holiday Hootenanny at the Soda Shop 2025

November 10, 2025

The holidays have hijacked the Simple Goodness Soda Shop, a family friendly cocktail cafe in Wilkeson, WA, with this year looking jollier than ever for the annual holiday tradition- despite a town in crisis. This year’s plans may come as a surprise in a year that has rocked the small town, after the permanent closure of the Fairfax bridge in April reduced tourism and business revenue by up to 50%.

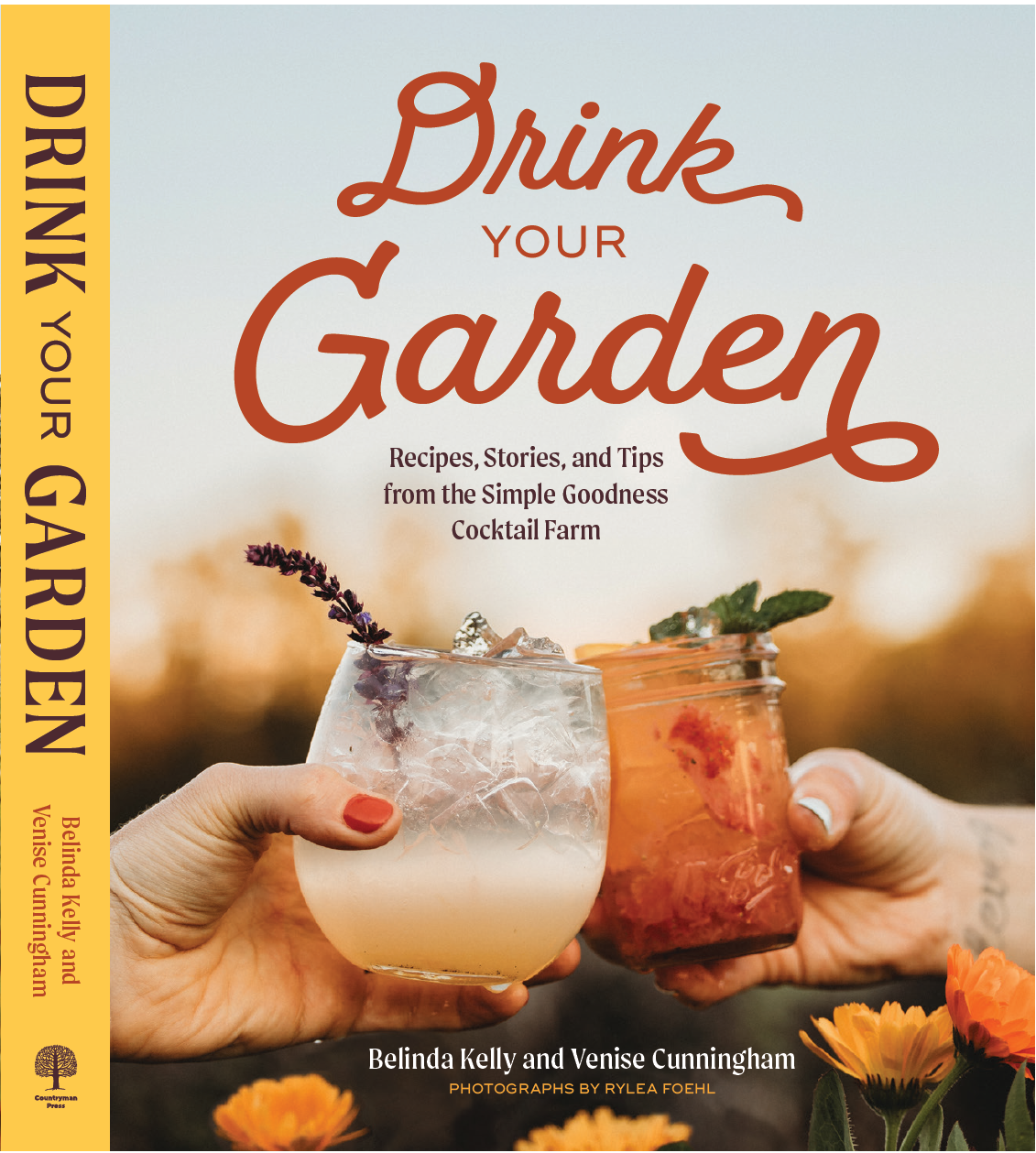

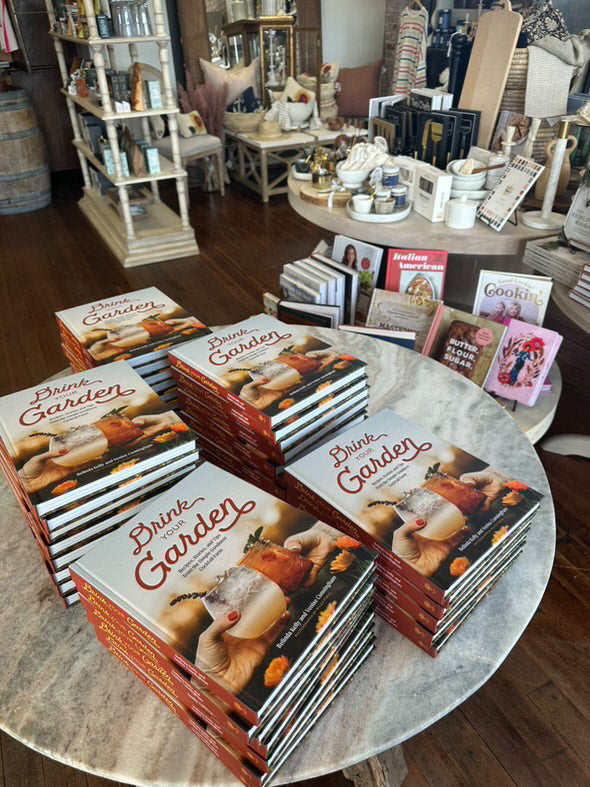

Book Launch: Drink Your Garden: Recipes, Stories, and Tips from the Simple Goodness Cocktail Farm

April 01, 2025